Laura Lykins, Laura M. Cornelius, Lyda Burton Conley, and Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin — These were early Native American women lawyers (or students of law). Historical newspapers identify these women and offer culturally revealing descriptions of them.

21 August 1898 — Cincinnati Enquirer

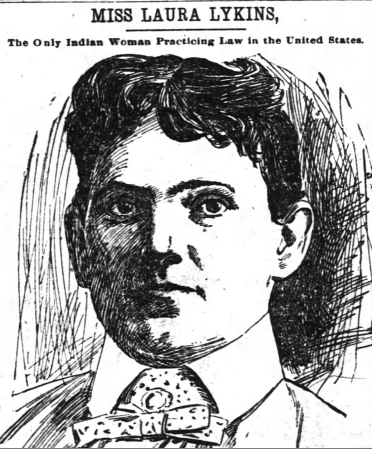

“Miss Laura Lykins — The Only Indian Woman Practicing Law in the United States”

There is only one Indian woman who is a practicing lawyer in the United States. She is Miss Laura Lykins, a pretty half-blood Shawnee Indian woman. She graduated from the Law Department of the Carlisle (Penn.) Indian School in June last, and then went to Oklahoma City, where she has been admitted to the bar and is very popular. She is 28 years old. She was born on the Shawnee Reservation in Kansas. Her father was a brother of Bluejacket, the famous old Indian Chief, who died last winter. Her mother was a white woman, and her maiden name was Lykins.”

25 February 1906 — Minneapolis Journal

“Indian Girl to Study Law at Barnard: Miss Cornelius, of the Wisconsin Oneida Tribe, Wouldn’t Be Anything Else than an Indian, and She Wants to Prevent a Great Tragedy — Wrong Ideas of White People.”

“Miss Laura M. Cornelius, a full-blooded Indian of the Wisconsin Oneida tribe, has taught in the government Indian schools, and now an intense desire to help her people, whom she loves, admires, believes in, has brought her to New York to study law at Barnard college, where she enrolled Feb. 1.

Miss Cornelius is unmistakably Indian in features and build, and ‘I am glad of it,’ she says.

She is tall, lithe, wiry of frame. Her complexion is olive without color; her abundant hair, worn parted and drawn loosely back from her face in a heavy coil behind, is glossy and black; her eyes, very dark brown, are soft and kindly, rather beadlike and glittering, after the popular notion of what Indian eyes should be like.

As with most persons who believe they have a mission to perform, Miss Cornelius’ personality suggests indomitable courage and sincerity. Her dress is disappointing; the picturesque touches one expects having been sacrificed to conventional fashion rules. But in most other respects she is faithful to Indian traditions and characteristics.

Not Weaned from Her People

‘I would not be anything but an Indian,’ she declares proudly. ‘I am not weaned from my people and never will be.

‘More schooling than usually falls to the lot of an Indian woman and more contact with the Caucasian artificiality and insincerity have graduated me into what might be called a polite Indian, and the process, I sometimes think, has taken a lot out of me.

‘The sincerity and simplicity of the Indian nature are crushed back as soon as he or she must do as the rest of the world does. The Indian living in a reservation can’t be anything but a reservation Indian — he can’t be himself.’

‘Well, naturally, under such conditions he hasn’t much chance to swing a tomahawk,’ it was suggested.

‘It is always like that,’ returned Miss Cornelius wearily. ‘Those who know little or nothing about the Indian remember only his deeds of violence while on the warpath and forget his magnanimity, his high sense of justice, his sincerity. They think of all Indians as a nomadic people. They do not understand that we have strong home ties and are a loving people.

‘And they forget, too, that the tomahawk was the Indian’s one weapon of warfare, just as guns are the approved and much more deadly weapon of other peoples, and that the tomahawk was used in the way most suited to the weapon.’

Praises Her Father.

In answer to a question, Miss Cornelius continued:

‘I owe much to my father’s ambitions. He, too, was ambitious to help his people; he himself struggled for an education and couldn’t get it.

‘He went out and worked at manual labor with the whites in order to get money to educate himself and then after all sent the money to help those at home. With his own earnings he bought a small farm in Wisconsin near Green Bay, within the reservation, of course, and there I was born, my father later moving to the very borders of the reservation that I might attend a white school.

‘From the cradle up I was impressed with one fact — I must get an education. And that I did get it was not at all surprising. Most Indian women, if they had the same opportunities, would do exactly as I have done.

‘At the country school for white children I won a scholarship which gave me a course in an Episcopalian seminary at Fond du Lac, and afterward I studied a short time at Stanford university. I have taught in the government Indian schools and traveled more than once across the country in the interests of my people.

‘No, I am not an Episcopalian. I do not pin my allegiance to any particular denomination or creed. My religion is this: I believe in God, my minding my own business and in hustling for what one wants.’

‘What things do you want for your people, and how do you expect to turn your legal knowledge when acquired, to their assistance?’ Miss Cornelius was asked.

‘I dread answering those questions,’ was the hesitating reply. ‘I can say this much, however, that the cause which makes me willing and happy to undergo anything, if only it can be advanced, is in itself so grand that it pushes personal considerations to one side. But unfortunately most people have so little understanding of the Indian situation that it is very difficult to give in a few minutes talk a correct impression of how I, an Indian, stand toward it, and how I mean to work to assist it, how I live for almost no other purpose.’

America’s Greatest Tragedy.

‘To my mind the Indians are heroes who are living today the greatest tragedy ever know, and the transition of the Indian marks the grandest tragedy America will ever know.

‘We are a passing people. Never again will the Indian be reinstated as himself. What is more, the people who have brought about these conditions are unintelligent so far as knowledge of the Indian temperament and character go. They don’t know us; they don’t know what it means to be killed alive.

‘I am sick to death of the idea that because you feed the Indian and put him in clothes and send him to school the Indian problem is solved, when the fact remains that thus far it is the Indian alone of all the American people who portrays a forecast of extinction.

‘The point is this: We have parted with — been obliged to part with — certain things, many things. Will the higher civilization, so-called, to which the Indian has been introduced, compensate for these things — that it has compensated?’

Civilization Detrimental

‘As practiced in behalf of the Indian, the higher civilization has been detrimental to his well being, you think?’

‘I certainly do. In traveling across the continent I have had this end constantly in view; to become thoroly [sic] acquainted with every class of people who make up America, to study how you solve your industrial and social problems and learn the fundamental principles by which the country is governed.

‘With the knowledge thus gained, combined with the legal knowledge I am here to get, I want to frame and to have put into actual practice a medium of statehood between the present Indian reservation conditions and American citizenship. This medium must, of course, be established on an economic basis, and I believe firmly it can be done. The only way to resuscitate a dying people is to bring life, industrial life, into their homes.’

‘And so far you think they have not experienced this industrial life?’

‘No. Between the rational system and American citizenship is a big gulf which the Indian does not know how to bridge. The hotbeds of educational institutions alone cannot prepare the Indian for this change, nor teach him how to take so long a step.

‘And I don’t mean to say that unaided I can do this work, but I certainly intend when my law course is finished to make other persons do it or help me to do it, whether they are Indians or whites. I have attempted nothing yet.

‘I Want to Do.’

‘At one time I had a marvelous ambition to write; but the more I live the more I know that words, words, words are futile. I want to do, not to preach.

‘There are about 270,000 Indians in the west, and I can’t bear to have them little by little swallowed up by the scum of the American population. If the Indian is to continue to amalgamate with the whites, let it be at least with his equals in sterling traits of character and intelligence.’

Asked what, in her opinion, was the greatest lack in reservation life, Miss Cornelius answered:

‘Industry. There is not motive, no incentive, no reward in the nature of the reservation for the man who will work.’

‘And you thing this condition may be changed?’

‘It must be changed or we will die.’

When speaking of her prospective course at Barnard college and her stay in New York, Miss Cornelius admitted that she expected to enjoy both.

‘I have made brief visits to New York twice before and I have several friends here to save me from homesickness. I love study, and in addition to law I may take up some other branches of study; for one of my ambitions is before long to have a big school of my own in the west for my own people.

‘As to the desirability of New York as a place of residence I have made one discovery already: The life here tends to crush out individuality.'”

Miss Cornelius did not become a lawyer; she remained an activist throughout her life. For a summary of her life, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laura_Cornelius_Kellogg

23 September 1906 — Des Moines Register

“Will Fight For Ancestors’ Graves: Indian Maid, a Lawyer, to give Battle in Courts.

Resists Government Order; Says Bones of Her Ancestors Shall Not Be Disturbed.”

“‘One hundred thousand dollars would be no inducement whatever in buying my consent to the desecration of the graves of my parents.’

So spoke Miss Lyda Conley of Kansas City, Kas., following the passage of the Indian appropriation bill, in which was included an order for the sale of Huron cemetery, an old Indian burial ground, for park purposes in Kansas City, Kas.

Miss Conley’s ancestors were of the once famous Wyandotte Indian tribe. She recently graduated from a law school, and is probably the only Indian maiden in the practice of law in the United States.

Kansas City, Kas., from the viewpoint of sentiment, is one of the most historic and interesting towns in Kansas, with the possible exception of Lawrence.

The parent town was the Indian village Wyandotte. The tribe of that name came to Kansas in 1843 from Ohio and Michigan. They bought the land, comprising 23,000 acres, from the Delawares who had preceded them. There were but few fullblood Indians among them. They were an industrious and religious people, and led in the civilization of the new country. In 1856 the Wyandotte gave up their tribal relations and became citizens of the United States. In the same year the town of Wyandotte, with the spelling changed to the French form, was formally organized. It lay entirely north of the Kaw.

In 1868, Kansas City, Kas., was laid off south of the Kaw, on land then heavily timbered. Now it is the site of the packing houses and other industries and is known as West Bottoms. Armourdale, to the south and west of this district, and containing all of the large packing houses on in another district, was incorporated in 1882.

Interesting Huron Cemetery

In the heart of Kansas City, Kas., now embracing Wyandotte and Amourdale, on the principal business street, broad, level, straight Minnesota avenue, lies a block known as Huron place, named for the one-time powerful ancestors of the Wyandottes. This block is unoccupied save for the Carnegie library, standing to the east of the center of its east half, a few business houses on its northeast and northwest corners, a church on its southwest corner, and the foundations of a new hotel going up on its southeast corner.

This east half block has been graded down many feet, but the western half is left in its original height, and is the site of the old Huron cemetery, the burial place of the founders and early settlers of the town. Most of the monuments bear date of the decade following 1844. In these ten years there were 400 burials. Under the monuments, undisturbed by the traffic noises, sleep the city’s fathers, Chief Tauromee, Chief Splitlog, the Armstrongs, the Northrups, the Walkers and the Clarks. All of these are further commemorated by streets and avenues bearing their names.

The larges and handsomest of the monuments was erected to the memory of a daughter of Silas Armstrong, the great quarter-blood chief of the Wyandottes, who was also president of the original Wyandotte Township company. The inscription on the granite shaft tells its own pathetic story.

ANTOINETTE

Daughter of

SILAS AND ZELINDA ARMSTRONG

and Wife of

T. B. BARNES

DIED OCT., 1882

Aged 24 years and 7 months

And Her Infant Daughter.

Under this a stanza so dimmed by time as to be nearly illegible is followed by the quaint couplet:

Thou wast too good to live on earth with me.

And I was not good enough to die with thee.

In the next enclosure, under a granite shaft, lie the young wife’s parents, their inscriptions bearing a later date. Silas Armstrong’s epitaph recites, among other virtues, that he was ‘a devout Christian and a good Mason.’

Other handsome monuments are those of the Northrups, Andrus B. and Hiram M., shafts of red granite, and are a considerable distance apart. These are a few of the monuments now standing.

Many of the small headstones lie prostrate, mostly broken. Some of the graves are only to be detected by depressions of the ground, many of these so grass-grown that they are not seen till the foot sinks into them. A path leads right over one grave — that of a young woman.

An aged custodian wanders about or sits in the shade of the walnuts and oaks. It was found necessary to have a caretaker to keep out the rowdies, who might carouse, or the ball playing street urchins. A few cows peacefully browse over the grass so far as the radius of their tether permits.

Rise in Value Ominous

And it is on this resting place of the Indian dead, because of its great rise in value, that the white man has cast covetous eyes.

During the last congress a proposition to transfer Huron cemetery to Kansas City, Kas., for a city park was incorporated in the Indian appropriation bill. This was done primarily, it is said, at the request of the council of a portion of the Wyandottes, who, in 1868, moved to Indian territory. Some of these had resumed their tribal relations, and time and space having weakened the hold of the cemetery on their affections, they allowed their council to take this action. The bill authorizing the sale passed.

The land was placed under the care of the secretary of the interior to be sold ‘under such rules as he may prescribe.’ The bill provides that the remains shall be removed to Quindaro cemetery, which, however, is not an Indian burial ground, but belongs by treaty to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

In case of a sale, some of the Indian survivors had planned to buy some two acres about twelve miles from the city and remove their dead to it, building a large vault for the unknown dead, and putting up appropriate monuments to their own. They further intend to invest a sufficient sum that the income may keep up the cemetery after they, too, are gathered to their fathers.

But others of the Indian citizens of Kansas City, Kas., say they will not sign away their right. The treaty of 1856 secured Huron cemetery ‘to them and their heirs forever,’ and they argue that though the Indian territory people, having resumed their tribal relations, are bound by the action of their council, they themselves not being so bound, will have to sign as individuals, and this, for one, Miss Conley declines to do.

Ancestor Captured by Indians

Many years ago, when Ohio was a hunting ground, Miss Conley’s great-great-grandfather, whose name was Zane, was captured by the Wyandottes. Though he was only 18 years old, preparations were being made to burn him at the stake, when the chief’s young daughter made a plea that he be saved for her husband.

This condition was accepted, and the youth was allowed to go to his home to say goodbye to his people. His family tried to persuade him not to return to the dusky maiden, but his word, and possibly his heart, was given, and he went back to the tribe.

Mrs. Conley’s grandmother was a beautiful white woman, and she herself is only one-thirty-second Indian. In 1902 she graduated with honor from the Kansas City School of Law, and is prepared to fight her case.”

Conley took her case “all the way up to the United States Supreme Court.”

For more on Lyda Conley, see

Kim Dayton, “Trespassers Beware! Lyda Burton Conley and the Battle for Huron Place Cemetery,” 8 Yale J. Law & Feminism (1995), Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjlf/vol8/iss1/2; and

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyda_Conley

8 March 1929 — Courier-Journal

“Indian Girls Score in Work; Woman Who Studied Law at 49 in Charge of Bureau Transportation”

“From tepee to concert stage has not been a difficult step for Indian ‘princesses’ who have flung aside war paint for rouge. The way has been a bit more difficult for daughters of Indian chieftains and others who have chosen careers in the business world.

One of the most outstanding examples of an Indian girl who has achieved success is that of Mrs. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, who was born in a Chippewa tepee in North Dakota and now is in charge of transportation in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Though her hair is grey, her eyes are as alive and bright as in the days when her father, who was one-quarter French, urged her to mingle with white people and learn their ways.

Seated at her desk in the Department of the Interior, Mrs. Baldwin took time to tell of her career.

‘I took my law course at the Washington College of Law when I was 49,’ she says, her bright eyes snapping. ‘I believe that when opportunity comes a person is never too old to take advantage of it. Anything that I have accomplished is due to the fact that I am an Indian, not in spite of it.

‘My grandfather was Pierre Bottineau, a noted scout who went with the Lewis Clark expedition into the Northwest. My own father, John B. Bottineau, was one of the first justices of the peace in Minneapolis. He started the town of Red Lake Falls. He always felt that he had been handicapped when a boy by being kept on a reservation and determined that his children should have an education and mingle with people. So we were sent to school.’ . . .

According to cold statistics at the bureau, the Indian ‘princess’ is only a myth and never has existed save in the sentimental imaginations of white men.”

For a very little more on Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, see

http://www.fofweb.com/History/MainPrintPage.asp?Pin=ENAIT037&DataType=Indian&WinType=Free and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Louise_Bottineau_Baldwin